Musing on Japan’s most celebrated poet leads to thoughts of 19thCentury battle

Describing the ‘Banana Tree’ pattern of Spode has rekindled some fond memories of Tokyo, where I lived for many years and wore out several shoes researching a guidebook.

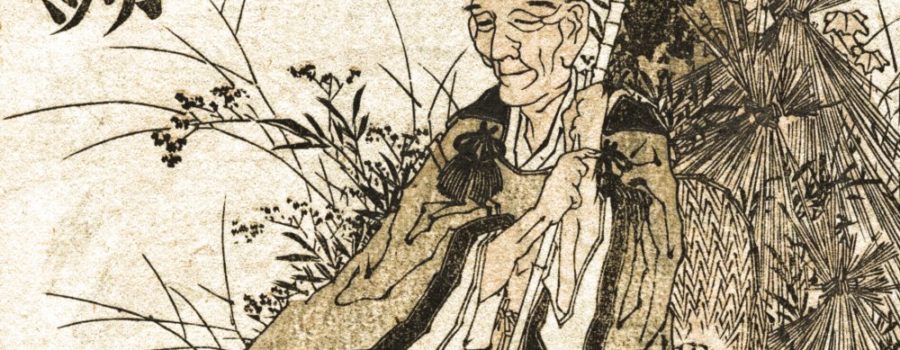

Japan’s most famous poet, Matsuo Basho (1644-1694), is named after a banana tree, or basho (芭蕉), that his disciple Rika had given him.[i]The basho was planted beside a rustic hut that followers built for the poet in 1680 in Fukagawa, an area of Edo (the old name for Tokyo) on the east side of the Sumida River. His new home became known as Basho An (‘basho retreat’) and he adopted Basho as his writing name.

Basho was the world’s greatest composer of haiku. Haiku are three unrhymed lines of five, seven and five syllables that originally were the opening verse, or hokku, of collaborative poetry called renga (連歌). Here is one Basho wrote in the spring of 1681, in which he worries that fast-growing miscanthus reed grass (ogi) will deprive his new banana tree of nourishment.

芭蕉植ゑて

まづ憎む荻の

二葉哉

bashō uete / mazu nikumu ogi no / futaba kana

‘We planted the banana tree, and now I hate the first sprouts of the ogi reeds’

The plaintive sound of rain falling on the huge, paddle-like leaves of the banana tree evoked poetic melancholy. Here’s a haiku, Feelings in my grass-thatched hut, Basho composed in the autumn of the same year:

芭蕉野分

盥に雨を

聞く夜哉

basho nowaki / tarai ni ame wo / kiku yo kana

‘A banana plant in autumn winds – I listen to the drops of rain fall into a basin at night’

By crossing the Sumida River, Basho was secluding himself from the literary hubbub in Nihonbashi, the commercial heart of Edo. It was from his thatched hut that he would set off on months-long journeys on foot. These journeys inspired him to create a new literary form, haibun, that combined fragments of prose with haiku. Basho’s best-known haibun is Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Interior). The Poetry Foundation says of his work that it is ‘rooted in observation of the natural world as well as in historical and literary concerns, engages themes of stillness and movement in a voice that is by turns self-questioning, wry, and oracular.’

The most famous haiku of all time, taught to all Japanese schoolchildren, is where Basho describes the sound of a frog jumping into a still pond.

古池

蛙飛び込む

水の音

furuike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizo no oto

There are hundreds of English translations. The most literal is: ‘Old pond / frog leaps in / water’s sound’

My own favourite Basho haiku is when cherry blossom fill the spring air in Fukagawa, and he hears a temple bell.

花の雲

鐘は上野か

浅草か

hana no kumo / kane wa Ueno ka / Asakusa ka

‘Cloud of blossoms / is that the bell in Ueno / or Asakusa?’

I happen to know these two temple bells. One belonged to Kan’ei-ji temple on Ueno Hill and the other to Senso-ji in Asakusa. Both are in Tokyo’s old shitamachi where researching my guidebook sometimes felt like urban archaeology.

Kan’ei-ji proved to be a special revelation. It was once a vast temple complex, built in the 17thCentury to protect the Tokugawa shogun’s new capital of Edo from evil spirits believed to emanate from the north-east. (Chinese geomancy also explains why Nara, Japan’s 8th-Century imperial capital, has Todai-ji, and Kyoto, imperial seat until the 19thCentury, the great Enryaku-ji, to guard their NE approaches.) Kan’ei-ji served too as a Tokugawa family temple where six of the 15 Tokugawa shoguns were buried, and a tradition soon evolved that its chief abbot was either a child or nephew of the reigning emperor. Kan’ei-ji once covered all of Ueno Hill and adjacent plains but nowadays most of its once 119-hectares sacred precincts host a railway station and such secular distractions as a park, zoo and museums

Kan’ei-ji was all but obliterated in the revolution of 1867-8 that overthrew the shogunate, “restored” imperial rule, and opened up Japan after two centuries of seclusion. Samurai who stayed defiantly loyal to the shogunate were known as shogitai (彰義隊, ‘battalion to demonstrate righteousness’) and they rallied around Kan’ei-ji and its chief abbot Rinnōji-no-Miya. Thanks largely to their British-made Armstrong Guns and Snider-Enfield rifles, imperial forces vanquished the shogitai defenders of Kan’ei-ji at the Battle of Ueno on July 4, 1868 and devastated most of the temple buildings (see the contemporary painting of the battle, and a photograph taken afterwards of the ruined Kan’ei-ji).  On September 19, Emperor Mutsuhito announced that Edo would be renamed Tokyo, or ‘eastern capital.’ Before the end of the year, Mutsuhito had made his first visit to Tokyo, where he occupied the shogun’s former castle, henceforth the Imperial Palace.

On September 19, Emperor Mutsuhito announced that Edo would be renamed Tokyo, or ‘eastern capital.’ Before the end of the year, Mutsuhito had made his first visit to Tokyo, where he occupied the shogun’s former castle, henceforth the Imperial Palace.

This was not to be the end of fighting. Enomoto Takeaki, who held the second-highest rank in the Tokugawa Navy, escaped to Hakodate in Japan’s northern island of Ezo with several warships and some French military advisers. (France supported the losing side in the Japanese civil war.) A ‘Republic of Ezo’ was proclaimed on January 27, 1869, and shogitai elected Enomoto its first president. The Ezo republic only lasted five months before Enomoto was forced to surrender to imperial forces. In September, Ezo was renamed Hokkaido.[ii]

Most of Kan’ei-ji’s land was confiscated by the new imperial government after the Battle of Ueno. Where the great hall and abbot’s residence once stood became the Tokyo National Museum. Kan’ei-ji is now confined to a parcel of land sandwiched between the back of the museum and railway tracks. Of the mausolea to the Tokugawa shoguns, only two gates and washbasins remain, the other mausolea having been destroyed in American air raids in 1945.

Some architectural gems miraculously survived revolution and conflagration. There is a gorgeous early 17thCentury Toshogu Shrine to the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu. (Toshogu roughly translates as ‘sun god of the east,’ the title Ieyasu was given after his deification.) Kan’ei-ji Kiyomizudo sits atop a little hill overlooking Shinobazu (‘Without Patiuence’) Pond, modelled by Kan’ei-ji’s first abbot to resemble Lake Biwa near Kyoto. The Kiyomizudo temple is itself a miniature of the famous Kiyomizudera in Kyoto. The strangest survivor of all is the original five-storey wooden pagoda of Kan’ei-ji, now reachable only after paying an entrance fee to Ueno Zoo. ‘The 1639 pagoda, a government-listed art treasure, stands in regal solitude behind the deer enclosure, its square moat plied by indifferent geese,’ I noted in my guidebook.[iii]

There is still the bell of Kan’ei-ji, though I cannot swear it is the exact same one Basho may have heard through clouds of blossom.

[i]This is not the variety of banana we are accustomed to buying at supermarkets. Basho, of which the botanical name is musa basjoo, produce inedible fruit. In English, they are known as ‘Japanese banana,’ ‘hardy banana’ or ‘Japanese fibre banana.’ Basho originated in southern China.

[ii]Enomoto was initially charged with high treason and imprisoned but was pardoned in 1872. Two years later he was made vice-admiral in the new Imperial Japanese Navy; in 1880 he was appointed navy minister. Rinnoji, the former abbot of Kan’ei-ji, escaped the Battle of Ueno and also ended up serving in the imperial armed forces. Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa, as he was known after leaving the priesthood, became a lieutenant-general in the Imperial Army, and took part in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5. His eldest son by a concubine was Prince Takeda Tsunehisa (1882-1919), whose only son, Prince Takeda Tsuneyoshi (1909-1992), helped organise the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, and whom I interviewed in 1984 for The Observer. Tsuneyoshi’s third son Tsunekazu (1947 -) was president of the Japanese Olympic Committee until 21 March 2019 when he resigned over a corruption scandal.

[iii]The American Express Travel Guide to Tokyo, Mitchell Beazley and Prentice Hall.

Recent Comments